Velzeboer spoke earlier this year at the 2009 Coal Operators’ Conference in Wollongong.

No stranger to the Australian coal industry, Velzeboer got his ticket at Appin and did early work at South Bulli. Now general manager of coal operations at ArcelorMittal, he was able to hold up the steel giant’s operations as an example of some basic challenges and as a mirror to some of the future needs of the Australian underground coal industry – from technical to social.

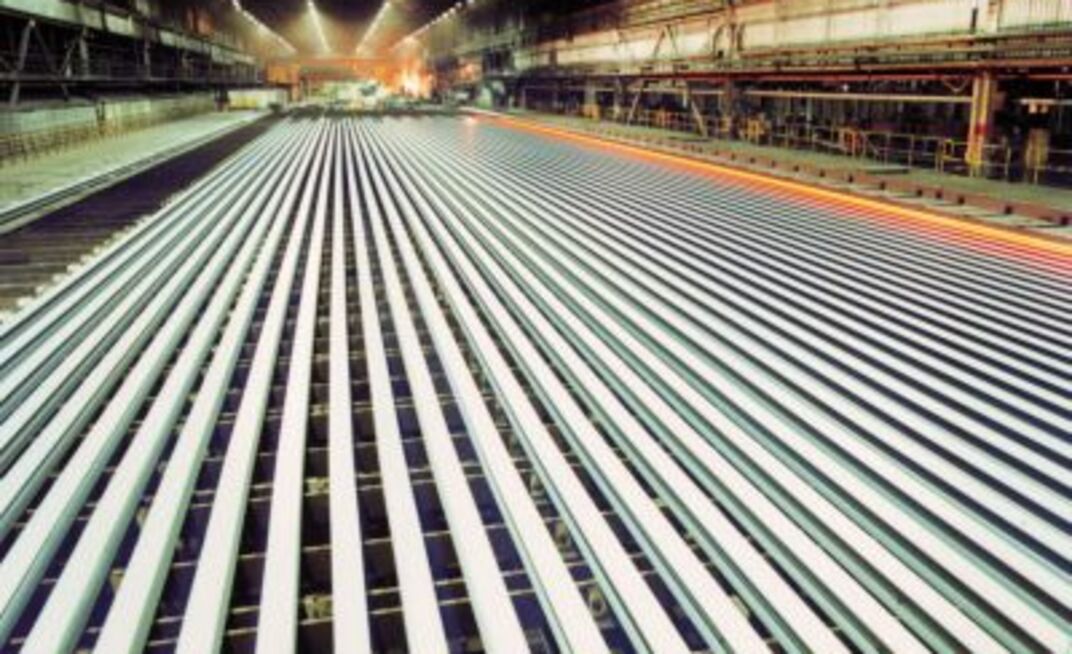

ArcelorMittal currently operates across several countries and has an annual output of about 20 million tonnes.

It has several surface and underground mines in West Virginia (US), three underground coal mines in Kuzbass, Siberia (Russia), and the Karaganda coal field in Kazakhstan.

The Karaganda coal field consists of 8 underground shaft mines, with an annual capacity of 12Mt. Each mine currently produces some 1.5-2Mt with about 2000 people.

Velzeboer said many of the seams experienced significant dips. The key technical issues were gas, outbursts, spontaneous combustion and past operational history.

He said one of the bigger issues ArcelorMittal had faced was the culture left over from the Soviet era, with its prescriptive form of management and strong “blame” culture.

“This usually results in the accident victim being considered the root cause of the incident,” he said.

For some time now, ArcelorMittal has been working on a focused program to break the historically poor safety performance through behaviour and modernisation.

Velzeboer said the basic technical issues associated with high gas levels, outbursts, improved ventilation practices and roof/rib support had been reviewed and were being addressed.

“The gas levels of some of the main seams are very high by anybody’s standards.”

Up to 25m3/t was recently measured for the D6 seam, which is also very prone to outbursts as the bottom section of the 6m seam contains a shear zone of soft and very fine coal.

“Our measurements also show that the top section of the seam may act as a significant gas reservoir, which possibly feeds the violent gas and fine coal release from the shear zone.

“In addition, the permeability of the seam is low, which makes effective pre-drainage difficult and so far ineffective.”

Velzeboer said work on the size distribution and shape particles from the different seam sections might allow ArcelorMittal to introduce a permeability enhancing methodology.

“It is also expected that by understanding the outburst mechanism, preventative measures and techniques can be developed to create a safe longwall panel development environment.”

At the mine, stone drives are first driven below the seam, from which the future gate road positions are degassed, before in-seam development is started. Velzeboer said despite a controlled environment, regular discharges of several tonnes of fine coal and over 1000m3 of methane still happened when drilling the pre-drain holes.

And that’s before they even start mining.

“Gas make during mining is a major problem, as is management of the goaf gas. With background values at the face of 0.8 per cent methane, there is little room for any additional release during production,” he said.

“Recent trials of cross measure drilling and gas extraction are proving very positive, allowing a more controlled gas management to take place. Goaf edge values of 0.3 per cent and purity considerably in excess of the explosive limits within the vacuum range are some of the physical achievements.

“Success in this area will not only allow a better gas capture in the extraction infrastructure, but also enable the ventilation system to be simplified to manageable and operationally comprehensible proportions.”

Velzeboer said luckily the Kazakhstan inspectorate and the unions were open minded to different approaches to methods of work, and the introduction of “western” techniques.

“I have always regarded the inspectorate as a friend, who is competent and can advise and act as part of his legal duties. This, in my view, is a major advantage Australia has over the American system, where the recording of violations appears to be a KPI.

“I believe that the issues and problems are too complex to play a cat and mouse game. By all means the inspectorate needs to be the stick, but the door also has to be open to allow progress to be made.”

He said another of the major operational challenges was keeping development ahead of the longwall given the amount of stone drivage.

“We still use steel arches supplemented by roof bolts. When questioned, the argument is sometimes voiced that arches are easier to put up than bolts. In a geotechnical benign environment there appears little justification for arches just to hang the pipes on. With some basic computer simulation, the case for more bolting may readily be made.”

He said compared to their western counterparts, operating from a mine planning point of view was also difficult given few software tools were currently available in Russian.

With his sharing of the difficulties faced in Kazakhstan, Velzeboer urged others in the industry to share their experiences for the greater good.

“I encourage the free interchange of ideas, theories and experiences at the operational level.

“All of us in the industry have a vested interest in promoting safe working and achieving manageable conditions of coal extraction. No company has the right to keep this to themselves for short-term commercial gain.

“The stakeholders are not only the shareholders and employees, but also the community, which no longer tolerates unduly hazardous working conditions anywhere.”